While There is a Soul in Prison

Kelsey Westbrook

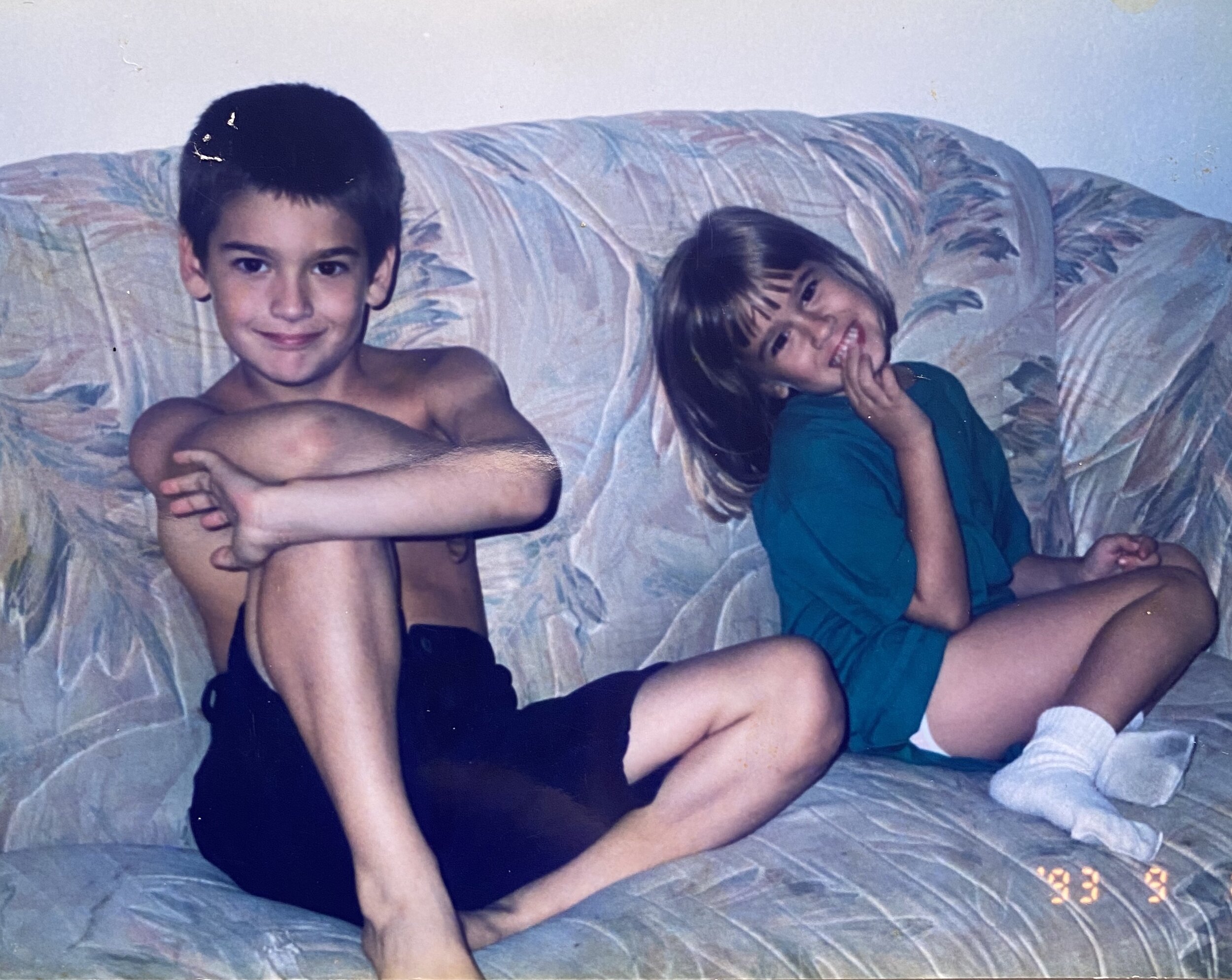

Covered Bridge Road was the winding, canopy-covered back road my brother and I took to high school every day of my freshman year. He was a senior at the adjacent, connected alternative high school, and even though I knew only one other student when I began at my school in the fall of 2002, I was wide-eyed, eager, and oddly confident. That confidence stemmed greatly from the notion that I was the little sister of a senior boy who was fiercely protective of me, and seemed to have all his teachers wrapped around his finger. He was a mischief-maker but charming to boot. Every morning, I’d load my embroidered, bright orange L.L. Bean backpack into the trunk of his white Honda Prelude and we’d set out on our twenty minutes of freedom.

My brother, Brandon, loved his Honda Prelude. He also has always loved to push the limits of, well, everything. For those twenty minutes, we had no authority to report to and no one to tell us to pump the breaks. We’d listen to Bone Thugs ’n’ Harmony and he’d fly around the corners of Covered Bridge — oncoming cars would often honk, clearly knowing it was a kid tearing around these looming curves, often only inches away from a plummeting fall (Sorry, Mom). I’d clutch the side of the passenger seat, trying to hide the fact that my stomach had dropped, because I never wanted to seem uncool around Brandon. He’d always sense when I was scared, though, and look over smiling widely. “I got you, Kels,” he’d say, and shift gears to slow down just a bit. We’d talk about his girlfriend or my friends or if I were interested in anyone at school yet and he’d always remind me he’s there when and if I needed him to make sure they’d treat me right. In those moments, I felt free with my brother. Although I was scared of the speed at times, I felt safe with him. I felt close to him, which I deeply longed for. I was his friend.

These are also some of the last moments I remember being blissfully unaware of what would come to be. Today, my brother sits in solitary confinement at Little Sandy Correctional Complex in Eastern Kentucky, nestled in the mountains near West Virginia. He’s serving a 27-year sentence for non-violent drug charges.

The more I’ve learned about prisons, the more I have been able to heal my relationship with my brother and advocate for his humanity, and the humanity of all those incarcerated.

I mention that his charges are non-violent only to provide context to this story, not because I believe he is more deserving of compassion than a person that has committed a “violent” crime, which could be any number of things. The prison industrial complex has taught us from a young age that all of these humans deserve to be locked in cages, but as a lawyer friend shared with me many months ago, this kind of rhetoric ingrains a “deserving binary” into our heads. When we hear these kinds of stories, and we see that someone is convicted of non-violent charges, that makes us believe they don’t deserve to be where they are, but other folks do. When, in actuality, abolitionists believe that no one deserves to be subjected to the kind of inhumane torture that goes on behind the walls of the United States prison system. To understand these nuances is to imagine a world without policing and prisons. To learn of these atrocities is to believe in transformative justice. The more I’ve learned about prisons, the more I have been able to heal my relationship with my brother and advocate for his humanity, and the humanity of all those incarcerated.

Just after those moments of freedom with Brandon in the Prelude, my memories of my adolescence become clouded with the trials of a family being ravaged by the opioid epidemic. Shortly into my high school career, my father fell deeply into opioid addiction. He lost his job, had several massive overdoses, and, I later found out, introduced my brother to drugs at the age of 14. Our home and cars were repossessed, and my mom, my younger brother and I had to move in with my aunt to stay in the same school district. Brandon, who had since graduated, stayed with my dad until the foreclosure went through, and my blissful childhood home became overrun with my dad and brother’s drug network and friends. I once walked into my old room to get a CD I’d left behind, and atop my daisy-covered comforter set were several large machine guns and bags of cocaine. A poster of Justin Timberlake on the pale yellow walls loomed over the artillery. I looked around and noticed my stereo system was gone — pawned, most likely, like most everything else — and I shut the door and walked away.

Even knowing that, my brother doesn’t blame my father for where he is today. Despite their disease, they had a beautiful relationship and perhaps their addictions brought them far closer than I could ever be with my father. I remember so often being jealous of them — like they had a secret, a shared bond that no one else could understand. While Brandon sadly shares the genetic disease of addiction, I do believe he was thrust into it violently at a young age without his consent. It’s almost as if he didn’t have a chance. Our story isn’t special. Millions of American families have been destroyed by the war on drugs, and it seems these tragedies have only gained a shred of public empathy and awareness once they began happening to white families.

“Imagine walking into your bathroom, shutting the door, and not leaving for seven months, and people bring your food and the phone to you through a hole in the door,” said my brother last year, when I asked him to talk to me about solitary confinement (a note: since then, he has done far longer in “the hole," and the United Nations has banned the use of solitary confinement for more than 15 days). He knows that his life is happening on the outside. His children, ages 13 and 14, are growing up, becoming their own incredible humans. His siblings and mother are growing, too. The world is changing, but he can’t see it. You are breathing, but are you truly living? Not to mention the deadly encounters that come with being incarcerated, and Brandon has had many.

Brandon has been stabbed in prison multiple times. He’s been “hog tied,” as he described to me, with both his hands and ankles cuffed and then a wooden stick slid through the cuffs, his body hanging upside down like a pig on a spit heading to solitary. The Corrections Officers would carry him on this stick, shift the cameras accordingly, and slam him against the wall on the way to a chair where he was pepper sprayed repeatedly. He was transferred to a different prison in the middle of the night in March of last year, when he was told he was exposed to COVID-19. When he arrived at the new prison, he was kept in a conference room in isolation with seven other men for five days without toilets, mattresses, or phones, and was forced to stay in the clothing he was “exposed in” and to eat food with his hands. When I asked an advocacy group I’m connected with how long they thought he’d be in there as I tried to locate him and the Department of Corrections continually lied to my mother and me about his whereabouts, they responded, “when there’s too much feces on the floor.” Brandon had COVID-19 in November 2020, when the virus ravaged the prison at an alarming rate.

My father died of a heroin overdose in 2013. The last thing I ever said to him was, “Stay out of my life until you get better.”

That phrase runs coldly through my veins and I see his torment when I close my eyes. I won’t be taking that path with Brandon. I was allowed to protect myself back then, and now, I am allowed to choose compassion. I choose to embrace all the things I’ve learned over the years and all that my family has had to overcome — all that I’ve had to overcome. I choose love. I choose redemption.

There were two representatives from the parole board “at” the hearing. Perhaps the most jarring and inhumane aspect of the hearing was, as my brother pleaded for his life, one of them continued eating from the comfort of what seemed to be her home. Click, click, went the plastic spoonfuls of yogurt on her teeth, audible through my speakers, between berating diatribes about criminal behavior and accountability.

Throughout the entirety of 2020, Brandon, my mother and I prepared for his parole hearing that took place on December 22nd. Our relationship has evolved so greatly in the past two years that I truly knew in the depths of my soul that he was ready. We had a flawless parole plan in place — a two year sober living program that included trauma therapy, a rehabilitation program, job training, reintegration programs, and more. I threw myself into advocating for his release, leaving no stone unturned. Dozens of letters were sent on his behalf, his bed at the facility was ready for his release, I was appearing at his hearing along with the program director from the facility he’d be paroled to, and so was my mom.

He could feel it, too. He was coming home for Christmas this year. All in all, Brandon has done nine years of his 27-year sentence, with a six-month stint out of prison in 2015. In total, he has spent years in solitary confinement. Surely, the parole board could see this, too — that this person was ready to see the outside world, to be a functioning and contributing member of society, that he has the support he needs to stay away from recidivism. Doesn’t it cost more to imprison this man than to allow him to enter this private program with far greater resources than the Department of Corrections? Any rational human had to see this was the case.

That was the mistake I made, though, assuming anyone that wishes to grant the fate of a man’s life as their occupation possesses a shred of humanity at all. Clearly, my experience with the DOC had taught me nothing. These people are cogs in a machine designed to oppress the most vulnerable communities, and they aren’t able to see my brother for who he is, or who he can one day become. I attended his hearing on Zoom (COVID-19 restrictions have prevented any parole hearings from happening in person for some time), and watched perhaps one of the most traumatic events of my lifetime unfold before me on my rose-colored MacBook. They brought him in in handcuffs behind his back and around his feet — they wouldn’t even un-cuff him to be able to hold his statement he put so much time into writing. A Corrections Officer splayed his handwritten papers out on a table before him. There were two representatives from the parole board “at” the hearing. Perhaps the most jarring and inhumane aspect of the hearing was, as my brother pleaded for his life, one of them continued eating from the comfort of what seemed to be her home. Click, click, went the plastic spoonfuls of yogurt on her teeth, audible through my speakers, between berating diatribes about criminal behavior and accountability.

After he pled his case, they took no more than five minutes off camera to deliberate. Even though Brandon was wearing a face mask, the anguished expression that came over him when they told him he’d be deferred another year is something forever burned in my memory. To be so close to freedom, to seeing your children’s faces in person, to tasting the air outside and touching the earth beyond what’s within the walls of a prison . . . that is a kind of pain I don’t know, but I have seen first hand time and time again.

I’ve spent so much time being an advocate for my brother that I’ve neglected to see the limbo the cycle of incarceration leaves me in, as his loved one, as well. My agony lives somewhere between how much I have done for him (is it enough?), what is within my power to continue to do, and how guilty I feel every day for simply living my life as a free woman. Incarcerating my brother has robbed me of so many moments of joy, of course because I don’t get to have him in my life day to day, but also simply because I bear the burden. I ask myself so frequently, “why do I get to experience this beautiful [thing/moment/day] when my brother languishes in torment?” Why should I get to feel love? I think about him, tortured within those walls, and it breaks me wide open. Just this weekend, I celebrated a birthday, ate cake and got showered with gifts by my friends and partner. And every few bites of that vegan chocolate cake, I closed my eyes and shattered. We are all born with the weakness to fall — that’s human. I’ve made mistakes, but I didn’t fall quite as hard as Brandon. How am I more deserving of a chance at a life? What kind of purgatory does that leave me in, as a person that loves him, when every moment of goodness has a shadow that looms just overhead? My brother wants me to feel joy, he wants to hear about my life, he supports me unabashedly. But the place that lies between not truly living as a family has a way of reminding me, even in the most beautiful moments, that someone I love is locked in a cage right now.

“While there is a soul in prison, I am not free.” - Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut said, “while there is a soul in prison, I am not free,” and that’s an ideology we all must reckon with now. It’s been decades since the war on drugs began, and so many white families are just now grappling with it. Black and brown families have long felt the emptiness at holidays, they’ve kept the stacks of letters stamped “INMATE MAIL,” they’ve felt the unjustness of this world far before I was ever born. Their loved ones have been the vessel for this cruel system to sail through time largely unnoticed, or denounced, by white communities. It’s true that white folks often speak up when we are finally affected by these atrocities -- when our families are ultimately destroyed by the prison industrial complex and other white supremacist systems that eventually impact us all. It is my hope that by telling these stories, we do not center our whiteness, but shine a bright light on the suffering that has taken place long before we found the strength to speak out.

I am grateful that, somehow, Brandon is still able to find hope. I can’t say that if I were in his situation, I would have survived this far. But he’s strong. He’s got a wonderful sense of humor. He buries himself in books and exercise to pass the time. He wrote me just two days after his hearing:

Kels!

Hey! Well it’s Christmas Eve and I’m watching it snow out the window. Looks like it will be a white Christmas this year. We’ve gotten about 3-4 inches outside and it’s coming down fast. It’s only about 7:00PM. Remember back in the good ole’ days, going over to Gran & Papaw’s and getting to open presents? And I mean way back, like Texas good ole’ days. The house on Bandera and the big house on Brushy Creek Trail. Before any of us knew how fucked up life could be. I miss those days. Good times, but when I get out, we’ll have to start some new traditions up again. I miss the normalcy of it. When I get out, you are going to be sick of me! I just want to help others. I won’t stop until I make you proud.

What my brother doesn’t realize is that I am already so proud to be his sister. For so long, and particularly when my father died, I thought I’d lost him, too. Addiction took over and the pain of it all was simply too much. Redemption, even from so far away, is a powerful binder amongst siblings. And, even though I was proud to be his sister on those wild rides in the Honda Prelude so long ago, our storied past on those roads isn’t what either of us are clinging to now. I think we can see the life ahead, the new traditions we’ll make one day. They’re further away than we’d hoped they’d be. And a system that’s working just as it was designed — to incarcerate Black, Brown and poor folks at an alarming rate — is a mountain we’ll continue to climb. And, in doing so, we must advocate for every single human behind bars.

“Tell my story,” Brandon wrote, when I asked him about writing this piece, “because we’re helping all the guys in here. So write the story. Tell all my stories. I love you, Kels. You make me want to try.”

Kelsey Westbrook (she/her) is a queer bisexual spirits professional, freelance writer, and non-profit organizer. Along with her career as the Beverage Director & Events Coordinator at NoraeBar, Kelsey’s writing has been featured in national publications including Bourbon+ Magazine, Difford’s Guide, Churchill Downs Magazine, and for iconic spirits brands including Diageo and Sazerac - Mr. Boston. Kelsey is the founder of the non-profit Saving Sunny, a community outreach and animal welfare organization. She is passionate about social justice, liberation, and her hobbies include cooking, travel, dog cuddles, and weightlifting.